https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/fall-2019/authors-of-their-own-stories?fbclid=IwAR14om4QHPSgt0TALyItmCN2QWMxF3xN09d8vg3V_h40LnfQEkSiMwTuoM4

Authors of Their Own Stories

When children’s author Vanessa Brantley-Newton spoke about seeing her identity reflected in literature for the first time, her audience nodded in knowing agreement. Brantley-Newton was addressing elementary students at Tapestry Charter School in Buffalo, New York, as part of the school’s project “I Am the Author of My Own Story” and a Teaching Tolerance Educator Grant.

Brantley-Newton described how, as a young person reading the classic picture book The Snowy Day, she felt a profound sense of validation and belonging. She eventually decided to pursue writing and illustrating children’s books full time. A simple moment of recognition had set the course of her entire career.

Among the listeners that day was Leah White. A parent and teaching partner at Tapestry, she had come to learn more about representation in children’s literature. For White, the issue was personal. “It is very hard for us to find books that relate to our situation,” she says. Dontae, an 11-year-old Tapestry student, is White’s cousin. White’s mother was raising Dontae, but when she passed away in 2017, he came to live with White. She now has full custody as his legal caregiver.

“We talk about unique families, how there aren’t a lot of books in the world about them,” she says. “It would be really nice to pick up a book and show Dontae that even though our family is different, what brings us together is that we love each other. A lot of times our kids aren’t seeing these things.”

White wasn’t the only adult at Tapestry considering the role of representation. As a reading specialist, TT grantee Kaylan Lelito watched the stories that had long been taught at Tapestry fall flat with her students.

“When I worked with students from different backgrounds,” Lelito explains, “often they would say when we were reading with them that they weren’t really interested in the books, that they didn’t see themselves.” Students of color comprise 74 percent of Tapestry classrooms, but in an inventory of their shared book room, Lelito found that only 17 percent of guided reading texts contained one or more characters of color.

To further explore this dissonance, Lelito surveyed her students to find out more about their reading experiences. The results were unsettling: Roughly half of her students didn’t see themselves reflected in the stories they read. Forty-four percent said they never found books about a neighborhood like theirs, and 40 percent said they never found books featuring families like theirs.

National statistics tell a similar story. While more than 50 percent of students in U.S. schools are children of color, only 13 percent of children’s books from the last 24 years contain “multicultural characters, storylines or settings,” according to a 2018 study conducted by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC). When the organization studied books published in 2018, they found more animal or nonhuman characters than people of color.

And these numbers only measure the presence or absence of representation—they don’t evaluate the quality of books that feature characters with underrepresented identities. “Just because you have 300 books about African Americans,” CCBC Director KT Horning says, “doesn’t mean all 300 of those are books you would recommend.”

For Lelito, the surveys of Tapestry students confirmed her suspicion: Students didn’t see themselves in the stories they read. And, because of this invisibility, they couldn’t relate. “The stories,” she recalls, “weren’t impactful for them. We wanted to find more books our students could see themselves in, and we were having difficulties doing that.”

With the help of her TT grant, Lelito ordered a wide selection of books from the children’s literature publisher Lee & Low Books, focusing on texts featuring characters with underrepresented identities. But Lelito didn’t just want to make better texts available to students—she also wanted to create space for them to tell their own stories.

After distributing the new books to third-, fourth- and fifth-grade classrooms and the library, Lelito turned to Tapestry’s librarian, Jennifer Chapman, for the second part of the project. Chapman worked with students to explore concepts like voice, flow and the sequence of storytelling. Then she had them create their own stories, with characters modeled after their own lives. “How does this reflect you?” she asked them.

A lot of kids would like to see books about families that are like them. If [every book] has the same storyline … they could feel invisible.

Writing their own stories resonated particularly well with older elementary students, who Chapman says were developmentally best prepared to process the project’s significance. “The youngest of our readers, they’re just excited about getting a book,” she says. But as kids age, they begin to pick up on the nuances of socialization and difference. “At about third grade,” Chapman explains, “a little switch happens. They start to spend more time actively looking for books that better reflect their lives.”

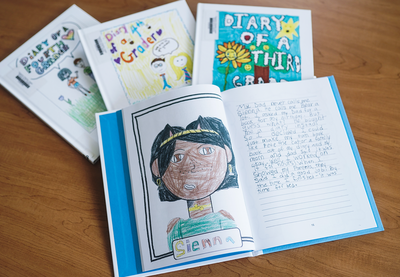

Once students finished their stories, Chapman and Lelito sent them off to a publisher, where they were anthologized in three collections. At a school community meeting, the stories were shared with family and friends. Third-graders titled their book Diary of a Third Grader; fourth- and fifth-graders followed suit. This fall, copies of the texts will be made available for checkout in the library, as well as in all classrooms.

For the final step in the project, students wrote persuasive letters to major children’s book publishers, articulating their need for characters and storylines that better reflect their experiences. “As educators of a very diverse population,” Lelito reflects, “it is incredibly important for us to help students realize that even at a very young age, they can have some control over how they are represented in the world around them.”

I don’t get to read about people like me.

“Dear Scholastic,” one third-grader wrote, “I’m just a kid, and I have a different heritage. I’m Muslim, and I don’t get to read about people like me. Other people should get a chance to read about different people, too. To me, learning something new about others makes me feel like I can connect with them and understand them.”

Another student’s letter articulated the problem that led to the project in the first place. “When someone reads a book,” he wrote, “they should be able to say, ‘Hey! That person looks like me!’ instead of reading a book and feeling bad about themselves because they look different. ...

So I suggest that you write some more diverse books.”

Ehrenhalt is the school-based programming and grants manager at Teaching Tolerance.

No comments:

Post a Comment